Reconstruction-era tombstones reveal ‘Stringtown’ history

When Burnet County Sheriff’s Deputy Jason Jewett researched the background of a historic gravesite in Oatmeal, he felt compelled to bring it to the attention of the greater Burnet County community.

“I was researching other history, saw this, read about it and kind of stumbled upon it while at work,” he said of his personal discovery in June of a historic black cemetery in the county.

“I found a suspicious vehicle. I noticed grave sites poking out from the bushes near the car,” he said. “The site was overgrown. It’s not a big site. It’s not very accessible.”

On closer inspection he examined several tombstones – one with a marker as early as 1877 and the most current one dated 1930.

His review of information from Burnet County Historical Commission records, online searches and a local historian revealed that the site was referred to in the past as the “Negro Stringtown Cemetery.”

“I just wanted to connect the dots between places I was seeing and the history of those places,” he said.

“Most of headstones were from the late 1800s.

“I was surprised that such a neat historical site was not in better shape, not being preserved better.”

About 70 graves are located on the site with 50 of them unmarked.

The community of Stringtown – formed by freed slaves during the post Civil War Reconstruction Era – was approximately four miles south of Bertram west of FM 1174.

“The cemetery is not marked. It’s not on maps. Descriptions in history books are kind of vague,” Jewett said.

Nonetheless, the upkeep of the site became critical to him.

“The (property) owners, who are in favor of keeping up with it, due to their age are unable to continue the maintenance, so I’m looking for someone to take up the torch, the baton and take care of it for the future,” Jewett said.

To that end he reached out to a long-time, multi-generational historian to find out more.

Burnet County Historical Commission board member Rachel Bryson launched into action providing Jewett with publications and documents to put together the historical pieces he requested.

Bryson, a retired journalist, explained the community’s history.

“There weren’t any plantations in Burnet County. So slaves were either brought from the south or some farmers in the area had one or two slaves,” she said. “Stringtown was established right after the Civil War.

“As soon as we got the word in Texas that they were free, they established what they were going to do,” she said of the June 19, 1865 date that Texas were read aloud the Emancipation Proclamation. “They formed the community. It was close to a creek.”

The name of the community was derived from the layout of residences and facilities.

“They built a church which was also a school,” she added. “They built little shotgun houses right next to each other. They did it like a little village.”

Reverend Sam Houston, a former slave, was a teacher and a preacher for the American Methodist Episcopal Church congregation.

“It served its purpose. They learned how to write and read. They went to church. They were a community.”

Stringtown residents forged a bond with their neighbors which transcended the racial issues of the time.

“The Oatmeal area had primarily German settlers, and they (Stringtown residents and white settlers) would invite each other backand-forth to gatherings,” Bryson said. “They were much more in tune with each other.”

In keeping with the spirit of the community, Jewett became determined to cultivate the same sentiment.

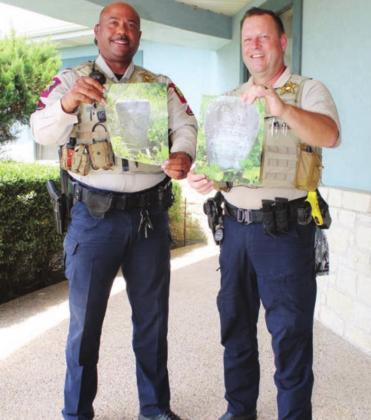

He asked fellow peace officer and friend BCSO Deputy Leon Ingersoll to assist him with his fledgling project.

Ingersoll saw his participation as a chance to not only preserve black history but “bridge the gap between law enforcement and the civilian population.”

“Both of us live here. We interact with the community. Just because we’re wearing a uniform does not mean we’re any different,” Ingersoll said of his unequivocal acceptance of the task. “I’ve dealt with people here compared to other agencies where I worked and they were more hostile. “Hopefully they (the com

“Hopefully they (the community) can understand what we deal with, and we can get a better understanding of some of the concerns or issues they may have.”

Both Ingersoll, a former U.S. Army veteran, and Jewett, a former Austin Police Department officer for 21 years, explained how such a partnership can provide an example that exemplifies shared human experiences. “I was in the military.

“I was in the military. I was a military brat. I’ve worked in different countries with people of different nationalities and customs – even my co-workers, some of them were from South Africa, Peru, Chile,” Ingersoll said. “If we can get along in different countries, different nationalities – under wartime or during confrontations – what’s going on here in the U.S. is small compared to what’s going on around the world in different countries.” During the time Jewett

During the time Jewett served at Austin PD, he maintained a residence in Burnet County for more than two decades.

“We had a pretty diverse police department in Austin – even people from foreign countries,” Jewett said. “Something like this project shows that the community can work together, like we do everyday.”

Both envision their effort could help heal past wounds and alleviate current unrest.

Ingersoll said, “It starts off here at a lower level. It could go as far as having annual events out there, barbecues, Juneteenth celebrations. Visitors can put their eyes on the cemetery.” Jewett added, “If we can

Jewett added, “If we can find descendants from the graveyard, that would be interesting. They may not even know (their family grave sites) exist.”

The historical commission has already taken steps to apply for a state historical marker.

“We’d love to have input from descendants and contributions for the marker,” Bryson said.

Jewett hopes to attract youth to participate.

“I see a lot of young passionate people, who really didn’t have a direction for that passion,” he said. “Using that energy and passion for something positive and constructive … they can pick up where people have been unable to take care of this cemetery and helped preserve black history in Burnet County,” Jewett said. “Why can’t we do it today if they could come together during Reconstruction right after slavery just ended.”

For more information or find out how to help the project, email StringTownGraves@gmail.com.